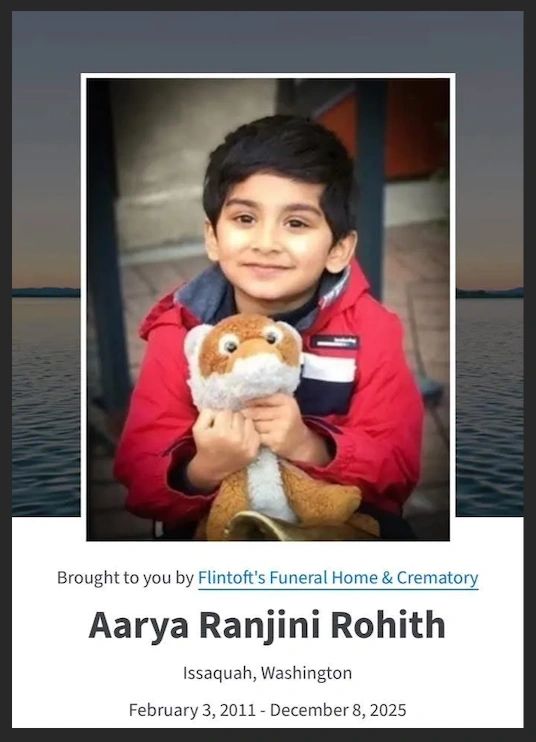

Aarya

Aarya Ranjini Rohith was fourteen years old when he died by suicide on December 8, 2025.

For the last five years of his life, Aarya did not simply grow up. He lived inside a legal process. His childhood unfolded through courtrooms, pleadings, evaluations, review hearings, and orders issued across two countries...

Aarya Ranjini Rohith Was 14

For the last five years of his life, Aarya did not simply grow up. He lived inside a legal process. His childhood unfolded through courtrooms, pleadings, evaluations, review hearings, and orders issued across two countries. Adults debated his fear, his resistance, his emotional health, and his future in legal language, while the conflict that shaped his daily life never truly stopped. This investigative article does not attempt to explain why Aarya died. It does not claim certainty where none exists. It does not assign legal fault. What it does instead is narrower, and harder: it documents what was placed before courts, what professionals stated in court records, what parents contested, and what remained unresolved while a child grew older inside a system that never found resolution.

A child at the center of litigation.

Court records show that Aarya was born in the United States in 2011 and spent his early childhood there. His parents separated in 2020, and litigation began shortly afterward in King County Superior Court in Washington State. As the case progressed, pleadings and declarations repeatedly described Aarya as a child in distress around his relationship with his father. In multiple filings, Aarya’s mother stated that her son expressed fear, anxiety, and resistance to contact. She described a child who struggled with transitions and who needed stability and protection. His father contested that account, denied that Aarya was afraid of him, and sought expanded parenting time, asserting progress, compliance with court orders, and a belief that the mother was interfering with the relationship.

These were not abstract disagreements. They shaped where Aarya lived, who he saw, and under what conditions. Yet despite years of litigation, the court never made a definitive factual finding about Aarya’s internal state. The question of whether his resistance reflected fear, trauma, manipulation, or conflict remained open. Instead of resolution, the case moved forward through a familiar cycle in family court: evaluations, therapeutic interventions, professional oversight, and repeated review hearings.

India, jurisdiction, and return.

In 2020, Aarya traveled to India with his mother. This was not unusual in itself. According to previously filed court records, Aarya and his mother had traveled between the United States and India regularly since his infancy, dating back to 2011. But this time, the travel became a jurisdictional fault line. The move to India was allegedly a protective step taken by the mother after years of documented abuse concerns. In India, Aarya lived within his cultural context and extended family support system. Multiple accounts in the record indicate that during this period, Aarya thrived, showing improved emotional regulation, stability, and relief from the distress that had characterized his early life in the United States.

Proceedings followed in Indian courts alongside the Washington case. In July 2022, the Supreme Court of India ordered that Aarya be returned to the United States. The Court emphasized jurisdiction, citizenship, and long-term upbringing, and directed that future custody disputes be decided by U.S. courts. At the time, only Aarya was a U.S. citizen. Neither parent held U.S. citizenship. Aarya’s father, however, had lived in the United States for more than fifteen years as a lawful permanent resident, and it was he who sought Aarya’s return under Washington jurisdiction.

The Indian Court did not make findings about abuse or safety. Its ruling focused on forum and welfare principles under Indian law. When Aarya returned to the United States, King County, Judge Janet Helson retained jurisdiction, and the Washington court’s supervision continued. What did not resolve with jurisdiction was the conflict itself. Records indicate conflict escalated upon the child’s return to the U.S.

Ongoing oversight without closure.

From 2022 through 2025, the Washington court maintained active oversight of the family. Parenting plans were modified. Parenting coordinators and therapists were appointed. Review hearings were frequent.The pleadings from this period reflect sharply different narratives. Filings submitted on behalf of Aarya’s mother continued to describe a child who was overwhelmed, resistant to certain transitions, and struggling emotionally. Filings submitted on behalf of Aarya’s father emphasized progress, cooperation, and concerns that the mother was obstructing reunification. Court filings reflect sustained efforts by Aarya’s mother to raise concerns about his fear, emotional safety, and resistance, including formal objections to recommendations and proposed placements she believed placed him at risk.

In October 2025, court-appointed reunification therapist Jennifer Keilin informed the court that Aarya had declined to participate in sessions with her, while continuing to see an individual therapist and psychiatrist not associated with the courts. The system remained in motion. Resolution did not arrive.

What the appointed parent evaluator found — and what she did not.

As the case moved toward a second trial, the court appointed Dr. Marnee Milner to conduct a parenting evaluation and assess the family dynamics. Her report became a central reference point for both parents, though each emphasized different aspects of her findings.

Based on court records, Dr. Milner did not conclude that Aarya’s father posed a safety risk. At the same time, her evaluation did not portray a healthy or uncomplicated relationship, According to the trial briefs summarizing her report, Dr. Milner identified rigidity in the father’s parenting style, a lack of emotional empathy, and inconsistent parenting. She described the father–child relationship as strained even before Aarya’s relocation to India and acknowledged that Aarya’s own perception of physical violence was part of that strain. She did not find evidence that the mother had engaged in parental alienation. Dr. Milner also noted that years of separation had deepened the rupture between father and son, making reunification more difficult. Her findings reflected a family system shaped by control, conflict, and unmet emotional needs, rather than a single, simple cause.

Both parents interpreted these findings differently. The father emphasized that the evaluator did not label him abusive and did not recommend abuse-based restrictions, and he expressed willingness to engage in parent coaching and therapeutic interventions. The mother emphasized the evaluator’s acknowledgment of rigidity, lack of empathy, and the child’s perception of violence as validation of long-standing concerns about Aarya’s emotional safety. What remained unresolved was how those findings should translate into daily life for a child who continued to resist transitions to his father, and who, even as professionals debated progress and pathology, was growing older inside the same unresolved conflict.

A system built on process — and the weight placed on professional authority.

By 2024 and 2025, the case record reflects a highly structured and professionalized system surrounding Aarya’s life. Parenting plans and review orders laid out therapy requirements, parent coaching, specialized treatment recommendations, supervised contact, phased “step-up” schedules, and continuing court oversight. Progress was not measured in lived experience so much as in compliance: completion of services, engagement with providers, and readiness to advance to the next stage. The proceedings unfolded in the King County Superior Court’s Special Set Family Court in Washington State, where Aarya, though the child at the center of the case, was not a legal party, yet the course of the proceedings often turned on his ability to comply with expectations set by adults and institutions.

A parenting plan entered in 2024 explicitly tied progression to Aarya’s stability and to changes expected of his father. The plan described the need for the father to demonstrate gains in empathy and understanding and empowered a parenting coordinator to recommend modifications to the schedule. It also stated that the father was expected to begin therapy to address “cognitive rigidity,” “lack of empathy,” limited insight, and anger toward the mother and her family, because those traits were described as interfering with his ability to interact effectively with Aarya. In October 2025, however, a court-related letter reported that Aarya had declined to participate with one of the appointed providers. At the same time, the letter noted that he continued to work with an individual therapist and psychiatrist, relationships described as being of “primary importance.” The system responded as it often does: by documenting engagement, non-engagement, and next steps.

The record, taken as a whole, shows a case constantly in motion: busy, procedural, always preparing the next intervention or review. But motion is not the same as resolution. The core questions about Aarya’s fear, emotional safety, and lived experience remained unsettled. Those tensions came into sharp focus in mid 2025. In an amended reply declaration filed on July 11, 2025, in advance of a July 14 review hearing, Aarya’s mother directly objected to what she described as recommendations being advanced by court involved professional Caroline Plummer. She wrote that Plummer recommended ordering Aarya to live exclusively with his father for two months, while limiting her own contact to four hours of supervised visitation per week, was “extreme and unnecessary.” She further stated that “the recommendations that Ms. Plummer is asking the court to consider are not rational” and did not reflect what she described as “significant improvements and progress” in the father–child relationship.

This was not vague language. It described a proposed reordering of the child’s primary home and a severe reduction of the mother’s contact, his primary safety net, a shift the mother believed was being pushed despite the child’s ongoing distress. The father disputed her characterization and supported the proposed changes. The court did not issue a definitive finding resolving the dispute. The relevance of these disclosures extends beyond this single case.

Caroline Plummer had previously been named as a defendant in a separate and unrelated civil lawsuit filed in King County in January 2022. That lawsuit involved different families, different children, and different facts. According to the complaint provided in the record, the plaintiffs alleged that Ms. Plummer pushed increased exposure and custody shifts, despite children expressing fear or lack of readiness, dismissed children’s reported distress as defiance, and advanced custody-time recommendations beyond her role that were later incorporated into coordinator reports. The pleading also described escalating distress in those children, including references to depression and suicidal ideation.

That lawsuit was resolved by settlement on September 5, 2023, without an admission of liability, and it is not presented here as proof of wrongdoing. But its existence, and resolution, is not anomalous in Washington family law. Reunification therapy has been widely likened to conversion-style interventions and has been linked in research and reported outcomes to psychological harm experienced by children.

A broader context beyond one case.

Across Washington State, journalists, legal scholars, advocates, and even legislators have documented persistent concerns about how family courts respond to allegations of domestic violence and child fear, particularly in high-conflict custody cases that are funneled into the industry by third-party court professionals. Guardians ad litem, parenting evaluators, reunification therapists, and parenting coordinators often occupy an extraordinary amount of power in these cases. These roles are court-ordered but privately paid by the parents involved, often at a cost of several tens of thousands of dollars over the life of a case. Their recommendations can shape residential placement, contact schedules, and even the framing of a child’s emotional responses, yet their training requirements especially around domestic violence, coercive control, and trauma, vary widely.

Investigative reporting has shown that in some cases, professionals appointed to assist the court may lack specialized expertise in domestic violence dynamics, even as they are asked to interpret children’s resistance, fear, or withdrawal. When that happens, a child’s distress can be reframed as defiance, pathology, or manipulation rather than examined as a possible signal of harm. A parent raising safety concerns may be cast as obstructive or conflict driven. The line between protecting a child and “interfering” with reunification can become dangerously thin.

Critics of the system have argued that this professionalized framework, designed to bring neutrality and expertise into family court, can instead create a feedback loop. Once a particular narrative takes hold, confirmation bias can be reinforced by reports, recommendations, and compliance benchmarks that leave little room for a child’s lived experience to interrupt the process. Instead of slowing down to ask whether the system itself is escalating harm, the response is often to add another intervention, another professional, another step-up plan.

This context matters because Aarya’s case did not unfold in a vacuum. It unfolded inside a system that has struggled, repeatedly and publicly, to distinguish protection from obstruction, trauma from resistance, and a child’s voice from the adult narratives imposed upon it. When courts rely heavily on third-party authority without clear guardrails, accountability, or trauma informed grounding, the risk is not just a bad recommendation. The risk is that a child’s fear becomes something to be managed, re-narrated and mitigated, rather than understood.

Aarya’s story cannot be separated from that larger reality. It is part of a pattern that has prompted calls for reform, greater oversight, and deeper humility about what courts and professionals can truly know about a child’s inner life, and how much damage can be done when the system gets it wrong. Earlier in 2025, a narrated attempt at reforming child safety and domestic abuse protections was solidified in legislation directed by the judges association.

Placed against that backdrop, the recommendations described in the dissolution court record do not appear in isolation. They emerge from a system that prioritizes process, progression, and professional authority, even when the child at the center of that process is struggling, withdrawing, or saying no.

December 8, 2025.

On December 8, 2025, Aarya Ranjini Rohith died by suicide. A custody status hearing was scheduled that same day. Submissions were filed. Court supervision had not ended.

There is no court finding explaining his death. There is no judicial determination assigning responsibility. There is only a record of prolonged litigation, contested custody, professional intervention, and unresolved fear, all still active when a child died.

What remains, and What is Gone.

The pleadings describe a child seen as fearful by one parent and as improving by the other. They describe evaluators identifying rigidity and emotional distance, without making abuse findings. They describe professionals recommending change, and parents fighting over what that change should look like.

What they do not show is certainty. Aarya’s death by suicide does not retroactively resolve the disputes that surrounded him. It does not prove one narrative true and the other false. But it does demand honesty about how prolonged litigation, contested custody, and reliance on third-party authority can shape — and sometimes eclipse — the lived experience of family court children who have no exit.

Aarya was not a court filing. He was not a jurisdictional question. He was fourteen year old child. He is now deceased. Rest in peace, Aarya.

Your life mattered. Your voice mattered. May what remains of your story help other children find safety, and may the systems meant to protect them learn to listen better.

— Gina Bloom